Practice 5: Enzyme immobilization of alpha amylases with sodium alginate

- Admin

- 30 may 2017

- 7 Min. de lectura

General objetive:

Immobilized enzymes by encapsulation technique with sodium alginate of the α-amylase extracts obtained by liquid (HF) and solid state fermentation (SSF) for later kinetic study.

Particulars objetives:

Use of extracts of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (HF), Aspergillus niger (SSF) and Aspergillus oryzae (86250-SIGMA-ALDRICH) to form the samples of beads.

Preparation of solutions at selected concentrations of sodium alginate and calcium chloride for optimum conditions.

Destruction of the beads with an acetate buffer of pH 3.5 for the release of enzymes.

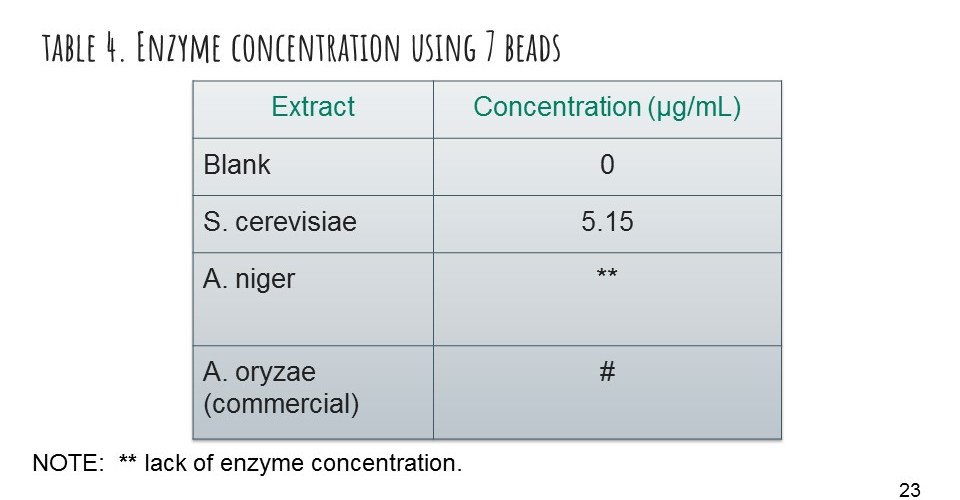

Quantification of total protein by means of the Bradford method for each extract.

Introduction

We know that enzymes have been used for years in the industry and many other applications; so that brings us to the increase for the need of higher qualities of an enzyme. According to (McKetta, 1993) commercial enzymes can be obtained in different purity grades, and they are sold in terms of units of their enzymatic activity, so the loss of this activity over time it´s a problem.

The importance of the need for storage and commercialization of this catalytic molecules, has led researcher to discover different techniques that can keep them save and stable.

Enzyme immobilization is one of these techniques, and basically consists in the confinement of an enzyme to a matrix/support different from its normal phase, where the absence of substrate and product is looked up to; also stated in (McKetta, 1993) the immobilization increases the number of enzyme molecules per unit area increasing the efficiency of the reaction.

The selection of a suitable polymer matrix/support is on base of one that can achieve the necessities for the enzyme we are looking up to immobilize, general characteristics of this matrix: •inertness •physical strength •stability •ability to increase enzyme specificity/activity •reduce product inhibition •nonspecific adsorption and microbial contamination Is important to emphasize that the matrix doesn´t interact in a molecular way with the enzyme; denaturalization doesn´t occurs.

Also there are lots of different techniques that focus on particular interaction between matrix-enzyme, where a variety of materials are used:

Adsorption: hydrophobic interactions.

Entrapment/encapsulation: physical restriction by covalent or non-covalent materials

Covalent bonding: chemical interactions between a carrier material and amino chains.

Affinity immobilization: exploits its specificity to join a certain material.

Cross-linking: non matrix method, intermolecular unions.

In practice the method used was encapsulation, so we will focus on this technique of immobilization. The concept of encapsulation has been based on the incorporation of a polymer matrix (Ertan et al., 2007), which forms an environment capable of controlling its interaction with the outside.

We know that microencapsulation is the technique of obtaining a barrier that delays the chemical reactions with the surrounding environment promoting an increase in the useful life of the product in agreement with (McKetta, 1993). And some common materials used in encapsulation are: alginate chitosan, collagen, carrageenan, pectin & gelatin, silica and nanoparticles.

Alginates, however, are one of the most frequently used polymers due to their mild gelling properties and non-toxicity. Alginate is a hydrocolloid, used as a matrix because of its ability to absorb water, easy handling and safety, and due to its gelling properties, stabilizers and thickeners. However, prolonged exposure to heat treatments and extreme variations of pH degrades the polymer, resulting in losses in gel properties (Kashima, 2017).

Sodium alginate is the most used because of its high solubility in cold water and characteristic sol-gel transition in an instant and irreversible way to the calcium ion.(Romero et al., 2013)

It is described as a linear hydrophilic polysaccharide, derived from brown algae formed by two monomers in its structure: •α-L-guluronic acid (G) •β-D-manuronic acid (M) According to (Ertan et al., 2007) these monomers are distributed in sections constituting homopolymers type G-blocks (-GGG-), M-blocks (-MMM-) or heteropolymers where the M and G blocks alternate (-MGMG-).

If in its polymer structure there is a greater amount of G-blocks, the gel is generally strong and fragile, whereas with the presence of a higher proportion of M-blocks the gel formed is soft and elastic.

So the gelation process occurs in the presence of multivalent cations (except magnesium) where the calcium ion is the most used by the food industry. Gelling occurs when a binding site occurs between a G-block of an alginate molecule that physically binds to another G block contained in another alginate molecule through the calcium ion. The visualization of the physical structure is called the "box of eggs" (Grant et al. 1973).

Figure 1. The eggs box structure shows where the carboxyl groups from alginate interact with the positive charge calcium ion.

The process is initiated from an alginate salt solution and an external or internal calcium source from where the calcium ion diffuses to reach the polymer chain, as a consequence of this union there is a structural rearrangement in the space resulting in a solid material with the characteristics of a gel according to (Grant et al. 1973)

The most commonly used calcium source is calcium chloride because of its higher percentage of available calcium, there are other less frequently used salts such as acetate monohydrate and calcium lactate (Romero et al., 2013).

Calcium ions have a positive two charge (Ca2+), and therefore must make two bonds to complete their electron shell and become stable molecules, and because they are taking the place of sodium ions, they must make an additional bond to satisfy this requirement.

Now we know that gelation kinetics, the degree of gelation, depends on the hydration of the alginate, the concentration of the calcium ion and the content of the G-blocks.

Figure 2. According to (Blandino et al.,1999) the hardness of the bead formed between sodium alginate and calcium chloride depends on its gelation kinetics, where the thickness and permeability of the matrix (bead) depends on how much time it remains in the chloride solution and its concentration. Finding a certain time where it grows and then a stationary point is reached.

The kinetics of the gelation process has been found to be influenced by alginate concentration, composition and particles size of calcium salt as reported by (Blandino et al.,1999). Also the longer MG blocks are in the alginate chains, the faster is the gel setting.

The spherification can occur in two different forms:

Spherification: Drop alginate into calcium chloride. The calcium moves into the drop, so gelation occurs inside the sodium alginate drop.

Reverse Spherification: Drop calcium lactate into alginate. Calcium moves into the alginate bath, so gelation occurs on the outside of the drop.

Below we will show the methodology carried out for the process of sperification with sodium alginate for different extracts of fermentations.

Experimental methodology

Results

Discussion

We made a comparative table with references of different articles that showed positive results in the encapsulation of enzymes with sodium alginate, we took the conditions of the process in all to choose our conditions.

Our conditions:

Concentration of sodium alginate solution (final): 3% w/v

Concentration of calcium chloride solution: 0.2 M

pH : 7

Temperature: 4 ° C

Gelification time (time of the beads in the calcium chloride solution): 45 minutes

These conditions in general were elected in base of the first article in the table (Ertan et al.,2007) because they report a enzyme activity of 96.2 % and an immobilized efficiency of a-amylase of approximately of 40%. Another reason why this article was chosen was for its clear procedure of the encapsulation method of the enzyme with sodium alginate and the different tests performed with different concentrations of sodium alginate for comparison.

About sodium alginate concentration

Initial concentration 6% w/v

Final concentration 3% w/v

During the procedure, we realized that the thickness of the mixture was hard enough to be extruded from the syringe.

So we changed initial alginate concentration to 3% w/v, to achieve a final of 1.5% w/v, where the mixture had a very natural flow.

There will be little diffusivity of the substrate in the pearl if they reach a thickness greater than necessary, we will check in the kinetics observing results

Gelification time in CaCl2

The beads were allowed to stand in calcium chloride for a time of 45 minutes. This time was selected because in order to obtain a sufficient hardness so the beads didn´t dissolved in the water.

According to the figure 2 in the section of the introduction, we can see how soon after 40 minutes, the stabilization of the pearl fails to increase a considerable range because it is a logarithmic function. This shows us that it is unnecessary to leave the pearls a longer time in the solution, as we would lose time without making a considerable change.

Protein Balance

Analyzing the 3 stages where our protein was manipulated:

I.Free enzyme

II.Gelification time in CaCl2

III.Immobilized enzyme

We use a simple balance to be sure that most of the encapsulated protein is inside the matrix.

free + CaCl2 = Immobilized

Immovilization efficiency

Will be calculated by a formula that appears in the article of (Ertan et al.,2007):

Table 7. Results from immobilization efficiency of each extract.

Conclusion

We achieved to immobilize alpha-amylase from 3 different enzymatic extracts, obtained from our fermentation practices: Saccharomyces cerevisiae (HF), Aspergillus niger (SSF) and Aspergillus oryzae (86250-SIGMA-ALDRICH).

We recognized the main variables that rule the encapsulation technique, to improve the process of encapsulation, like temperature, pH, concentration of the sodium alginate and calcium chloride solutions, and the time of gelification. Confirmed the presence of protein by Bradford total quantification test, with results of immobilization efficiency of 96.5%, the highest, of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, 88% of Aspergillus niger and 94.28% of Aspergillus oryzae.

References

Ertan , Hulya Yagar & Bilal Balkan (2007): Optimization of α‐Amylase Immobilization in Calcium Alginate Beads, Preparative Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 37:3, 195-204

Mahajan, R., Gupta, V. K., & Sharma, J. (2010). Comparison and Suitability of Gel Matrix for Entrapping Higher Content of Enzymes for Commercial Applications. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 72(2), 223–228.

Riaz, A., Ul Qader, S. A., Anwar, A. & Iqbal, S. (2009). Immobilization of a Thermostable á-amylase on Calcium Alginate Beads from Bacillus Subtilis KIBGE-HAR. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 3(3): 2883-2887.

Sardar, M. & Gupta, M. N. (1998). Alginate beads as an affinity material for alpha amylases. Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 7: 159-165.

Kumar, R. S. S., et al. (2006). Entrapment of a-amylase in alginate beads: Single step protocol for purification and thermal stabilization. Process Biochemistry, 41: 2282-2288.

Blandino, A., Macías, M. & Cantero, D. (1999). Formation of calcium alginate gel capsules: Influence of sodium alginate and CaCl2 concentration on gelation kinetics. Journal of bioscience and bioengineering, 88(6), pp.686-689.

Anbazhagan, M., Parthiban, S., Suganthi, C., Karthikeyan, S., S. Babua, K.M.. (2012). Optimization and immobilization of amylase obtained from halotolerant bacteria isolated from solar salterns. School of Bio Sciences and Technology, VIT University, Vellore 632014, India.

Salsac, A.V.,Zhang, L., Gherbezza, J,.M.(2009). Measurement of mechanical properties of alginate beads using ultrasound. Laboratoire Biomécanique et Bioingénierie. 19 `eme Congres Francais de Mecanique

S. H. LIN (1990) Gelation of sodium alginate in a batch process. Department of Chemical Engineering, Yuan Ze Institute of Technology, Neili, Taoyuan, Taiwan, Republic of China.

Romero, G.C , López – Malo, A. y Palou, E. “Propiedades del alginato y aplicaciones en alimentos” Temas Selectos de Ingeniería de Alimentos 7 (2013)

McKetta, J. (1993). Chemical processing handbook. 1st ed. New York [etc.]: Marcel Dekker.

Grant, G., Morris, E., Rees, D., Smith, P., Thom, D. (1973). Biological interactions between polysaccharides and divalent cations: The egg-box model.

Kashima, K., Imai, M. (2017). Advanced Membrane Material from Marine Biological Polymer and Sensitive Molecular-Size Recognition for Promising Separation Technology.

Comentarios